Monday, April 26, 2010

Saturday, April 24, 2010

Avid for Athens

You can help bring Avid Bookshop to Athens, Georgia, by voting for them in the Pepsi Refresh Everything.

Magnifico

This past week we received finished copies of foreign editions of a couple of our books: The Drop Edge of Yonder in French and Some Things That Meant the World to Me in Italian.

This past week we received finished copies of foreign editions of a couple of our books: The Drop Edge of Yonder in French and Some Things That Meant the World to Me in Italian.Friday, April 23, 2010

Our Bright Future

And then there’s a stew of Two Dollar Radio-related messages. There’s one from independent publicist Lauren Cerand, saying that she saw Erotomania: A Romance, a novel by Francis Levy, in the window at City Lights. I also have saved messages from nearly every one of the authors we’ve published at Two Dollar Radio over the last two years informing me that their author-copies have arrived. They sound satisfied, and what they have to say always makes me smile.

I remember talking with Larry Shainberg, whose book Crust we published last October. I was asking Larry about Samuel Beckett, whom he was fortunate enough to meet on a handful of occasions and befriend (Larry also wrote a Pushcart-winning monograph on Beckett for The Paris Review). Larry told me that he went to see Beckett in Europe, and the pair was returning to the hotel where Beckett was staying when the desk clerk provided him with his mail, which contained the author-copies of one of his books. I don’t recall that Larry mentioned which book of Beckett’s it was, but I remember him saying that it didn’t matter whether it was your first book or your fiftieth, there’s still that feeling of intense satisfaction and joy that arrives with finally holding your book in your hands.

As a publisher, I derive a great deal of satisfaction myself when the finished book arrives. Recently, when copies of Rudolph Wurlitzer’s second and third novels, Flats and Quake, which we’re re-issuing in a back-to-back edition, came from the printer I immediately broke out my camera and took pictures. Certainly, some of the glee could be attributed to the fact that the book looked as we intended: we were nervous about the flipped/upside-down pages.

I’ve learned that publishing is a drawn-out process that above all demands patience. There is that initial burst of enthusiasm after reading a remarkable submission, then the re-kindled energy over presenting the title to the reps at sales conference, but the real flood of excitement comes upon holding the finished product in my hands. That’s when it’s real, the transition complete, when I find its spot on the bookshelf in my office: it is now a book.

As a publisher we’ve dragged our heels in embracing e-books (or even acknowledging their presence). Through our distributor, Consortium, we’re able to partake in their parent company’s program, that allows publishers to make their books available electronically rather painlessly, albeit with a modest fee. But it took us at least eight months to sign the contract, and we’re still, now, months later, resolving any further contract entanglements with authors.

Part of my reluctance is my inability to resolve in my mind the bitter truth of what we’ll be stamping our brand upon. As a publisher, I know e-books are a cheaper product – both to produce and consume (providing you can foot the tab for the e-reader) – and I’m certain that writers do too. What makes anyone believe that readers won’t arrive at this realization as well? Once the honeymoon with their sleek new gadget ends, they’ll start to demand more for their money. As a commenter to Nick Harakaway’s blog post on e-books points out: “I wouldn’t pay more than $10 for an eBook, because at more than that, I want more than I’m getting. I want a dust jacket, I want something physical. There’s an inherent belief (and I agree) e should never cost as much as its old world equivalent. You really do get less.”

Gimmicks such as Simon and Schuster’s snigger-trigger “Vook” are just the tip of the iceberg. Soon, because of the lack of page-count constraints, e-books will come complete with deleted chapters, a writer’s and editor’s cut, and alternate endings. The result will resemble more a videogame fantasia than a traditional “book.” And I don’t want to read that.

As Emily Pullen, of Skylight Books in Los Angeles, so aptly points out in a blog post: “Creating digital literature and harnessing the medium’s unique capabilities requires a specialized knowledge of programming languages. As such, it is software engineers and computer programmers (the techies) who are best suited to use this new literary medium, not the traditional Writer.”

Most likely, it will be several years and rungs on the evolutionary ladder of the Vook before even its initial potential can be imagined. In the meantime, at Two Dollar Radio we’ll casually make our books available electronically. At our size, the potential fifty dollars a month from e-book sales can make a difference. But I don’t expect many messages from authors calling to share their enthusiasm at their e-books arriving. And I won’t blame them.

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Stickups by the Stuck Up

Bryan Charles’ “Wowee Zowee” and Shawn Vandor’s “Fire at the End of the Rainbow”

The latest from Continuum’s stellar 33 1/3 series of little rock ‘n roll books is Bryan Charles’ treatise on Pavement’s third album WOWEE ZOWEE. Charles, author of the funny and affecting novel “Grab on to Me Tightly as if I Knew the Way” (itself a Pavement song lyric; you could say Bryan is a fan), interviewed all band members and various label staff and recording engineers, venturing to Memphis and generally keeping his unyielding love for the band and the album stuffed into a mason jar of intrepid journalistic inquiry. The launch for Wowee Zowee will be held at Brooklyn’s WORD bookstore on Wednesday, April 21 at 7:30 p.m. Charles will read and sign and answer Matthew Perpetua of Fluxblog’s questions.

The latest from Continuum’s stellar 33 1/3 series of little rock ‘n roll books is Bryan Charles’ treatise on Pavement’s third album WOWEE ZOWEE. Charles, author of the funny and affecting novel “Grab on to Me Tightly as if I Knew the Way” (itself a Pavement song lyric; you could say Bryan is a fan), interviewed all band members and various label staff and recording engineers, venturing to Memphis and generally keeping his unyielding love for the band and the album stuffed into a mason jar of intrepid journalistic inquiry. The launch for Wowee Zowee will be held at Brooklyn’s WORD bookstore on Wednesday, April 21 at 7:30 p.m. Charles will read and sign and answer Matthew Perpetua of Fluxblog’s questions. Shawn Vandor’s debut collection of stories “Fire at the End of the Rainbow” is one of three coolly attractive books published by the Key West-based Sand Paper Press earlier this year. The press, in “limited operation” since 2003, recently ramped up production with “Fire” and two collections of poems: Stuart Krimko’s “The Sweetness of Herbert” and Arlo Haskell’s “Joker.” The trio is intended as a set, and they are certainly complementary in their Key West-esque peach, cornflower and strawberry pastel covers. All three Sand Paper Press authors toured the West Coast together this February and March. I can personally attest that Vandor’s deadpan delivery of the scatological little doozie titled “Manhood, a Cautionary Tale” at LA’s David Kordansky Gallery brought the damn house down.

Monday, April 19, 2010

Reality Bites

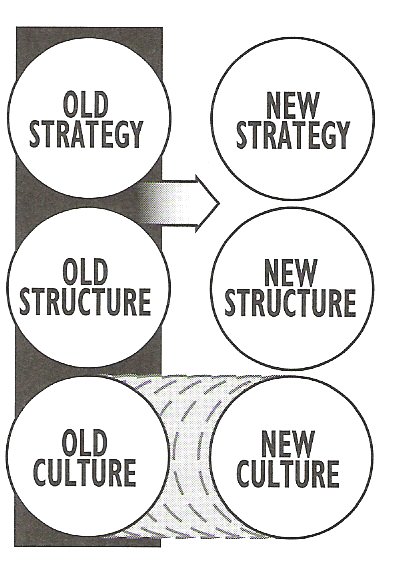

The New Culture

Saturday, April 17, 2010

Jersey Shore in the East Bay

San Francisco has many talented writers, and one of my favorites is K.M. Soehnlein. His first novel "The World of Normal Boys" was fantastic, funny, and devastating. Luckily for us, K.M. decided to revisit the characters from his debut romp with his new novel, "Robin & Ruby."

San Francisco has many talented writers, and one of my favorites is K.M. Soehnlein. His first novel "The World of Normal Boys" was fantastic, funny, and devastating. Luckily for us, K.M. decided to revisit the characters from his debut romp with his new novel, "Robin & Ruby."This Monday, April 19th, I'm thrilled to read in the East Bay with K.M. at the Ashby Stage in Berkeley. The evening is themed around "not your usual" beach reading, as some of Soehnlein's new book is set on the Jersey Shore. The stage will be decorated with a makeshift boardwalk and sand. Will it also stink like cologne and garbage to truly duplicate the Garden State? Hmmm. I guess you'll have to come play with us to find out for sure.

I'm going to read from "Termite Parade" which I just got the galleys for this week. It looks fantastic. To be honest, there won't be a lot of "beach" in my excerpt, though I guarantee some "not your usual."

The event starts at 7. They'll be serving "sex on the beach" to set the mood... classy. Maybe in true Jersey Shore style, we can drink them out of each other's belly buttons.

Come out and support Soehnlein's amazing new read!

Saturday, April 10, 2010

L'Age d'Or

Friday, April 09, 2010

Tuesday, April 06, 2010

The People Who Watched Her Pass By

Monday, April 05, 2010

Hating Beloved - the Post-Game Summary

by Scott Bradfield

In 2001, somebody called me on the phone six months before I was scheduled to speak in Berlin and asked what the title of my lecture would be. They were paying good money, so I felt I should try something new - a “personal essay.”

My desk at UCONN was covered with these terrible How to Teach Beloved textbooks I’d been picking up at used bookstores because, frankly, I had no idea how to teach Beloved. And I was getting frustrated. So I said, “I’d like to write about why I hate Toni Morrison’s Beloved.” The Berliners printed up lots of flyers, ran ads in newspapers, and six months later, I had cornered myself into writing this essay.

After the lecture, a young blondish Paul Verhoeven-looking Austrian man stood up and said, sounding a lot like Governor Arnold, that he was disappointed I hadn’t really blasted Toni Morrison, and that I should have kept my promise. Then he walked out.

I turned the lecture into a prose-essay the next year, when I taught a graduate seminar at UCONN entitled, “Literature and Crap: What We Like and What We’re Supposed To.” For two years, I sent the essay around to dozens of journals and periodicals, all of whom rejected it on one of two grounds:

1) they “didn’t get it”

2) they agreed that they didn’t like the book either, and agreed with most of the things I said, but they ”just couldn’t” publish it

The essay was eventually accepted by a young(er than me) critic and short story writer named Paul Maliszewski, who was guest-editing The Denver Quarterly. Paul accepted the essay, and subjected it to his version of close-editing - which was excruciating, never-ending, and, more often than not, really helpful. Shortly after the essay was published, Paul wrote me an e-mail which said something like: “Oh, and there’s this awkward phrase on page seventeen we still need to look at.” It was the only e-mail from Paul to which I never replied.

I have been snubbed several times since the essay appeared by people who wanted me to know it. At one dinner party, a colleague and his partner picked up their plates and left the room when I suggested that Charles Johnson (a good novelist and short story writer I have never met) had every right to say that he didn’t like Beloved (I don’t know if he did say that, by the way, but that’s what somebody had reported.) And still, every so often, I will meet an academic who will say to me, “Beloved is a very, very important book to me.” They say it completely out of the blue. Then they drop the subject.

The essay was never reprinted or made available on the internet. So I was glad that Eric and Eliza agreed to make it available at Two Dollar Radio, where we are all encouraged to freely love and hate books as we see fit. Even our own.

After the essay appeared in print in 2004, I received a few clandestine nudges and winks from people who told me they liked the essay, but that was all. Then, a few months ago, somebody sent me Wikipedia’s entry on The Denver Quarterly, which described one of DQ’s high points as the “published to acclaim” Morrison essay. (And I didn’t write the entry, I swear.)

I sent the entry to Paul Maliszsewski, who promised me he hadn’t written it either. Then he suggested that “published to acclaim” was probably a cliche, so we should cut it.

“Please don’t,” I replied.

Friday, April 02, 2010

Why I Hate Toni Morrison's Beloved

by Scott Bradfield

The first time I told someone that I had problems reading Toni Morrison's Beloved, she started yelling at me in a Marie Callender's restaurant in Dana Point, California. I had recently received my Ph.D. in English at U.C. Irvine, just a dozen miles north, and we were having what graduate students consider a "blow out" (food and beer) at a moderately-priced franchise restaurant; it marked the saying of our goodbyes before I drove my truckload of books to the heretofore unglimpsed state of Connecticut. This wasn't the first time that someone has yelled at me in a restaurant, by the way. I don't even think it was the first time someone has yelled at me in a Marie Callender's restaurant. But it was the first time anybody has ever yelled at me, at length and in volume, for disliking a book. Oddly enough, I didn't even hate Toni Morrison's Beloved at the time. I was just having trouble reading through its middle pages and seeing what the fuss was all about.

There are two reasons why the title of this essay appealed to me so much that I decided to write some pages to follow it up.

What's more, saying "I hate Toni Morrison's Beloved" may actually be unhearable. As an expression of personal opinion, preference, idiosyncracy, taste, what have you, I am not sure that people hear this statement in itself, since all sorts of cultural, social, and historical meaning gets tangled up with it. To take an obvious example, an Anglo-Irish non-denominational suburban guy such as myself will be "heard" in a variety of ways that he might never wish to be heard; and, whether he likes it or not, many assumptions will be inferred about his opinions on history, race, politics, power and so forth. Or, to dispense with the issue of race altogether (something that's not easy to do when discussing Beloved), I could even be accused of writerly bad faith. I mean, we writers are an envious lot, and here I am hating a book which has succeeded spectacularly in ways that none of mine ever have or, I can admit it now, ever will—such as winning a Nobel Prize for its author, appearing on Oprah and selling a gazillion copies.

I felt threatened by the success of a woman novelist because of my inborn inability to embrace her radically new perspective on history which could only be generated by all-embracing female heterogeneity; in fact, by disliking Morrison, I was validating many opinions that many female colleagues already held about me and the fact that I had completed my Ph.D. in a manifestly sexist English Department, since at least one member of my committee was a known sexist who had reputedly engaged in a long-standing affair with a female graduate student....

And so forth. It really did continue for a while, dredging up a lot of unspoken emotions. Some of them surprised me; others didn't. I won't belabor this conversation, or the way my statement was "heard" by an individual whom I liked, respected, and continue to be friends with. But I do want to place this anecdotal moment in the context of contemporary academic scholarship, since I don't consider it arbitrary or inconsequential. In many ways, it strikes me as surprisingly representative of contemporary scholarly thought.

1) I have trouble saying that I hate Toni Morrison's Beloved, mainly because I don't want people to think I am either a racist or a sexist, and;

2) people have trouble hearing what I think I'm saying.

As a teacher of literature, where does that leave me when I try to teach Beloved? If neither I nor my students, can express a simple statement of opinion or conviction, where does that leave us when called upon to explore even more difficult issues? And where does it leave the common reader who picks up books and puts them down again according to the many multifaceted, and deeply idiosyncratic reasons we all pick up books and put them down again?

#

In a sense, I'm writing about two different objects of reading. On the one hand, there is the specific book that I hold in my possession, a blue jacketed thirty-eighth printing Plume paperback that I purchased across the street from the University of Connecticut at the Paperback Trader. This is a limited, identifiable object. On the other hand, there is this, I don't know what to call it exactly, this illimitable presence, this "landmark of contemporary literature," this vast region of wisdom and light which stands over us in judgment, a manifest benevolence which can only be called

Toni Morrison's Beloved.

I've set these words off in twenty-point boldface type, which doesn't do justice to the way I see them projected on the screen of our cultural imagination. As I really see them, they flicker above and behind all our heads, just out of vision, emitting a vibratory thrum, like a neon sign. You can feel the words in the air before you glimpse them. To my mind, twenty-point type doesn't do these words justice. Thirty-point type, perhaps. Forty-point. But then I wouldn't have any space left over for writing this essay, there would just be page after page of

Toni Morrison's Beloved.

Which might be a little hard to take.

Toni Morrison's Beloved.

A silence falls over us in our divided spaces.

#

According to the MLA International Bibliography, since 1987 there have been more than five hundred articles published in respectably vetted journals on the subject of

And almost every one of them is laudatory in the extreme. Occasionally you might find an article which appears value-neutral—examining image-clusters or ideological configurations or whatever—but for the most part these articles never make a negative or qualifying statement about Beloved; and they almost always refer to it as a masterpiece, or one of the twentieth century's greatest novels, or something along those lines.

Take, as a purely arbitrary example (it's on top of the stack of books I have assembled in my office), the Ikon Critical Guide, edited by Carl Plasa. This survey of critical essays and topics contains interviews with Morrison, framing comments by the editor, and a fairly standard critical bibliography. Subtitled "The Student Guide to Secondary Sources," it is designed to teach students how to compare and analyze arguments, then extrapolate new arguments of their own. Like most books teaching you how to do something, it teaches you how not to do something as well. And what it teaches you not to do is pretty frightening.

The extract from Crouch, by contrast, is a denunciation of Beloved/Morrison, as vehement as it is both scurrilous and wrong-headed. Running thoroughly counter to the overwhelmingly positive critical reaction to Beloved, it is included here less in the interests of some spurious critical balance than as an illustration of just how highly charged debates about Morrison's work can sometimes be.

"Highly charged," indeed. I guess it's a good thing that even-handed critics like Plasa are around to help the cooler heads prevail; perhaps this is why he prefaces Crouch's review with a comment by Nancy Petersen, which accuses Crouch of "capitalizing on the desire of white readers to consume black women's tales of being abused by black men." (I'm sorry, but I have no idea what that means.) Plasa then takes every opportunity to misread or selectively quote from Crouch in order to make some pretty damning statements. At one point, he claims that Crouch, insensitive to the brutality of slavery, refers to the Middle Passage as little more than a "trip across the Atlantic." This is an inaccurate and misleading statement. Crouch doesn't appear to suggest anything of the sort, though he does argue that Morrison misreads historical events in order to validate modern presumptions, especially feminist ones. It's an argument worth considering by any serious student.

I must confess that I don't know much about Stanley Crouch. I saw him interviewed recently on PBS, so I know he's black; he writes for The New Republic, a so-called "neo-conservative" weekly out of D.C. which I have no interest in reading; and he clearly knows how to get up people's noses. His work may well reflect some serious cultural and political biases; but the same could be said of Plasa and his colleagues, pumping away on their critical Stairmasters. Finally, though, I wouldn't call Crouch's review of Beloved any more "wrong-headed" or irresponsible than any of the others reprinted by Plasa; at least he writes more clearly, and raises some interesting and contentious points—points that deserve, but don't receive from Plasa, fair-minded consideration and reply.

#

Here are some lessons a young student might learn from the first thirty pages of Plasa's book, thus equipping him or her for a high-flying career in literary scholarship:

1) Some white male and female academics consider themselves incapable of saying anything about Beloved—though this doesn't render them incapable of asserting that Toni Morrison represents "a major figure of our national literature";

2) Everybody who loves Beloved is "fully in step" with the vast mass of scholarship being produced today;

3) Anybody who disagrees with points 1) or 2) above is probably "scurrilous" and "wrong headed," and may well be pandering to white readers who like to see black women abused by black men.

That's quite a tutorial.

#

When I walk down the corridors of any literature department in any university anywhere in the world, I get the overpowering sense that my relationship to an individual book (in this case, my thirty-eighth printing trade paperback of Beloved) is overseen, and in some sense monitored, by this huge presence called Toni Morrison's Beloved, a presence elevated above us, in a region that we can't quite see.

#

Or I could have written about "Why I Hate Gunter Grass's The Tin Drum," which I simply never got through, or "Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children," which, sure, it's probably a very intelligent book and has lots to say about post-colonial rhetoric and so on, but Rushdie has a wooden ear and his sentences are, I'm afraid, just too angular and clunky. And while we're at it, let's add Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow to the list, and anything by William Burroughs or Jack Kerouac, and most of Saul Bellow, and more than half of Ulysses, and the entirety of Henry James's late period, and Vladimir Nabokov's Ada (which is nowhere near as good as Lolita or even his great early novel, Laughter in the Dark), and okay, you can probably hear it, I'm getting a little out of breath, I'm ranting, I'll stop. But I'm afraid this is what happens when I start exercising about all these books and authors I've forced myself to read, or failed to read, or could only read in order to teach for some survey course which paid my rent.

#

Consider my trade paperback copy of Beloved, purchased second-hand for $2 from the Paperback Trader in the late spring of 1999. It features an author photo of an attractive, middle-aged woman, along with some pretty impressive jacket copy, most notably:

Winner of THE NOBEL PRIZE in Literature

and a highly-placed quote from the important American reviewer, John Leonard, who says: "I can't imagine American literature without it."

#

Like many people who enjoy books, I have fond memories of being read to as a child. It is strange to think that while my parents did many things for me when I was growing up—fed and clothed and housed me—that I still remember evening bedtime stories with a special fondness. In my early years, before my brother was born, my parents guided me through large picture books—I especially enjoyed the ones filled with photographs of lions and tigers and zebras. Later, we read smaller pages with more words in them—books which I didn't understand sometimes, and didn't need to. There was something about the ritual warmth of reading that mattered more than what the words conveyed. It provided, in fact, a different sort of consensus: cuddling up around the book with my brother and one of my parents, I would listen to that night's chapter of Call of the Wild, say, or Alice in Wonderland, and ask endless questions about what it conveyed, and what might happen next. ("I don't know," my Mom or dad would explain simply, "we'll have to wait until tomorrow to find out, won't we?") Finally, after making sure I knew the title of tomorrow's chapter, and had glimpsed at least one of its illustrations, I went to bed with these weird visions of other worlds in my head. I might imagine my brother and me riding bobsleds across the frozen steppes, or sitting down to tea with the Mad Hatter, or leading Black Beauty home to her lost master. They weren't better than me, these books. They were inseparable from the imaginative life I lived in my home. They never spoke to my mind, but conversed with it.

I remember loving Moby Dick before I read it. What's not to love when you're five or six years old? This one-legged Captain driving his crew across the seven seas in search of a gigantic white whale? What a great book not to read. I even loved the movie when I was little (it was on par with "The Amazing Colossal Man," though it didn't give me so many nightmares), and I went on to purchase the Classics Illustrated edition at the local Rexall drugstore. I read and reread it, carrying it around scrunched up in my back pocket until it resembled the head of a mop. In fact, I read it so often and so intensely that, many years later, as an undergraduate at UCLA, I got away without reading the actual novel on at least two exams. I have many friends who love Melville, and I hope that the day arrives when I can say I like Melville as much as I loved that Classics Illustrated comic book. In my most subjective universe, that would be saying something.

I remember this space on the hall floor, surrounded by books I couldn't quite read, with great fondness. These books were far from objects of worship, and I played with them like toys, stacking them in interesting configurations—pyramids and forts and obelisks—and imagining what might happen if the characters they contained were to wander out of their books and move into one another's spaces. Would Ellison's Invisible Man be a match for the Invisible Man of H.G. Wells? Would Mailer's naked soldiers perform bizarre and unconscionable acts with Samuel Butler's flesh-bound travellers, very likely in a hot bath before bedtime? I played with these books and even developed a sense of commitment to reading them some day, when I grew up, because I wanted to know what was really in them and wanted them to know what was in me.

Whenever I think about books, or the act of reading, with pleasure, I always think about this time I spent alone on the floor with these books I couldn't yet read. It was the most enjoyable relationship with books I have ever known.

#

Something has happened to the reading of books in my lifetime. I don't want to sound like one of those cranky old men who say everything was better in my day, because I don't think it was. But the worst aspects of book-reading definitely have taken the place of the better ones. Our academics and critics select a few books each year (often written by their friends) as worthy of consideration without having read anything else; then they congratulate one another for liking the same books, or pick petty quarrels about which end of the book should be cracked first. Which book is more reactionary than the other two? Which undermines gender stereotypes more effectively, or unravels the always unravelling thread of language? At the end of the day, you don't feel anybody is talking about books at all. They're talking about themselves, and the disciplinary institution called, for want of a better term, literary culture. They're talking about their boring jobs.

When I think about all those huge indigestible books hovering up there behind us, I think about the statues on Easter Island that were erected by people we don't know much about. Statues bigger than us, more frightening, and more real than we're supposed to be, and while I think that I can live with the statues erected by somebody a few thousand years ago, I can't bear to watch my colleagues, my students, and myself, straining to erect more of them.

Books are about a lot of things: race, gender, the Napoleonic Wars, sex, death, food, social norms, social outcasts, social incasts, fantasy, fact, dreams, sadness, loneliness, elation, injustice, class, the Mason-Dixon line, language, stupidity, co-habitation and rage. But ultimately, they are about the process of reading them; they are about the things their authors have known and seen and imagined long enough to write them down. They are, by their nature, transitory experiences, just like our lives, and we shouldn't judge them, or be judged by them. We should only live with them, much the same way as we live with one another. We do not owe them respect or allegiance; we only owe them the considerable effort of trying to read them the best we can.

When I first thought up the title of this essay, I felt uncertain and defensive about it. But in the course of writing it, I have come to conclude that I don't mind hearing anybody say that they hate or love any book, or any writer. To hear people disagreeing about books, hating and loving them, doesn't make some of those people good and other ones bad. It doesn't sound like a bunch of "right wing" people arguing with a bunch of "fully in step" ones. It just sounds like the noisy contentious clash and accord of people reading. You see, it's my opinion that the most terrible statement you can utter is not "I hate X" or "I love Y." The most terrible thing you can say, especially to your students, is: "You must hate X." Or: "You must love Y."

Thursday, April 01, 2010

Avid Bookshop